This article was written by Yalitza Ledgister of the law firm of Attig | Curran | Steel, PLLC (I’m told a link to Yalitza’s bio is coming soon).

In June 2020, I promised that, in an effort to take a step towards ending the systematic oppression of Black veterans, I would hire a writer to elevate the voices of Black veterans, veterans of color, women veterans and veterans who identify as LGBTQI.

I followed through on my word: Yalitza’s column will be written for the Attig | Curran | Steel law firm’s “Taking Point” blog. Her first post appears here.

That law firm has agreed to syndicate her posts to a new column on the Veterans Law Blog®: The Real Veteran. On “The Real Veteran,” I and guest writers will explore what it really means to be a veteran. If you would like to submit an article to be published in the “The Real Veteran”, please click here to pitch your idea to me.

************ One day my son came home from school and, pointing to his brown arms, asked, “Mom, why can’t I have white skin?” After the initial shock and parent-fail slap wore off, I proceeded to explain to him the beauty in being different and the diversity of our family, rehashing the same things I was told years ago when I asked the same question. I immediately asked him if someone in school said something about his color, which he denied. Where would he get this desire from? We’ve always embraced our color in our family. Our gatherings are a huge melting pot of black to white with all shades in-between. I continued to scrutinize my entire life as a mom for signs of where I may have missed opportunities to make our son feel confident and proud in his skin. Even more distressing was examining everything in our home or activities that might suggest that white was more favorable. I took an inventory of all the books on our shelves, the shows I allow them to see, movies we’ve seen together, toys and superheroes they enjoy. I found nothing that screamed prejudice, but not enough that normalized the significant contributions of people of color.

A few months later, my husband and I snuck the children into the movie theatre to see Black Panther, their first PG-13 movie at 6 and 7 years old. There was something so healing about watching a well-made film about a Black superhero. During a familiar heroic scene of fighting that turned triumphant for the Black superhero, I glanced at my son. There was an inexplainable joy in his eyes. His face lit up in a brilliance as he saw himself on screen delivering the finals blows to the enemy in fearless heroism. It was a cathartic experience, releasing years of longing for a superhero that looked like us. The Black hero lives, but what does America do with his or her story? During World War I and World War II no Medals of Honor were awarded to African American soldiers. The Medal of Honor is the highest military award for valor, and it is publicly presented to service members by the President on behalf of Congress. This medal can only be awarded, “through conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of life above and beyond the call of duty” as stated by the Department of Defense. The Medal of Honor also comes with its courtesies and privileges including an additional monthly pension for recipients. Regrettably, our country’s long history and continued struggles with discrimination and racism doesn’t make exceptions for heroes. Even today, Black Medal of Honor recipients are few, and far between.

Digging for Heroes

In 2002, Congress called the Pentagon to review the war records of Jewish and Hispanic American veterans from WWII, Korean War, and the Vietnam War to ensure there was no prejudice in screening their citations for gallantry and valor.

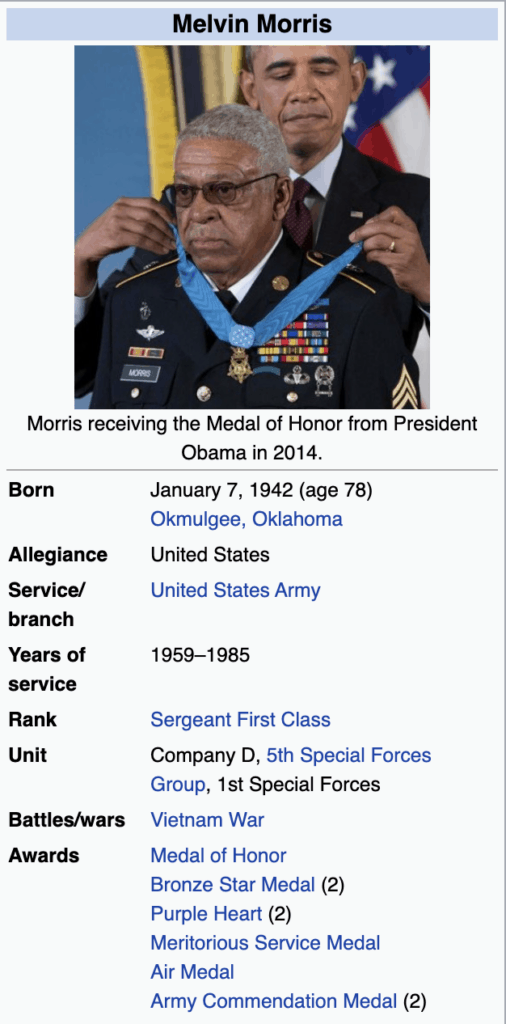

The review was ordered because evidence of discrimination and prejudices in the military emerged that created inequity among the awarding of military decorations. During this review, it was discovered that several other soldiers that were awarded the second-highest medal met the criteria for the Medal of Honor which included an African American veteran, Melvin Morris.

On March 18, 2014, President Barack Obama presented the award to nineteen minority Medal of Honor recipients who were passed over due to discrimination. Although their acts of valor and gallantry on the battlefield mirrored those of their white counterparts that were awarded the Medal of Honor, minority veterans were denied the highest honor even posthumously.

Staff Sergeant Melvin Morris’s Medal of Honor citation describes what took place on September 17, 1969 in the vicinity of Chi Lang, Republic of Vietnam when his affiliated companies encountered an extensive enemy mine field. They afterward came across hostile fire. When Sergeant Morris learned that a fellow team commander had been killed near an enemy bunker, he made his way to reach his fallen comrade. On his way to the bunker and charging through enemy fire, he assisted two wounded men and eliminated four other bunkers with hand grenades. He recovered the body of his friend and said last rites over him, then he was shot in the chest, arm, and finger.

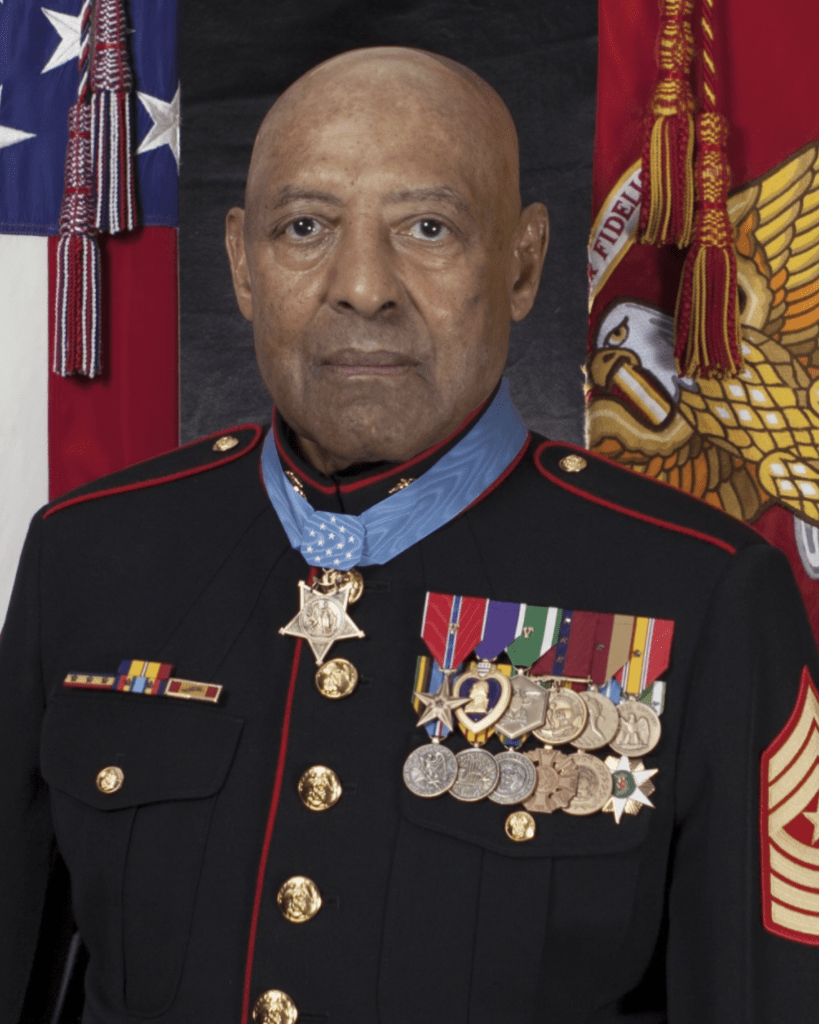

Sergeant Major Canley was the most recent African American service member to receive the Medal of Honor as of November 2019. He served in the Marines for 28 years and was awarded the Navy Cross for his heroic actions while serving in Vietnam in 1968. Sergeant Major Canley’s valor medal upgrade came after a fellow service member contacted Congresswoman Julia Brownley and asked that she recommend him for the Medal of Honor. It was not an easy accomplishment due to the five-year time limit for the award. The bill granting the waiver and upgrade was passed into legislation and he was presented with the prestigious medal five years later.

Retired U.S. Marine Corps Sgt.Maj John L. Canley, the 300th Marine Medal of Honor recipient, poses for a command board photo at the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia, Oct. 18, 2018. From Jan. 31, to Feb. 6 1968 in the Republic of Vietnam, Canley, the company gunnery sergeant assigned to Alpha Company, 1st Battalion, 1st Marines, took command of the company, led multiple attacks against enemy-fortified positions, rushed across fire-swept terrain despite his own wounds and carried wounded Marines into Hue City, including his commanding officer, to relieve friendly forces who were surrounded. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Lance Cpl. Morgan Burgess)

Still Waiting…

There are more heroes out there.

Heroes that were willing to risk- even to give up- their life for a friend or more.

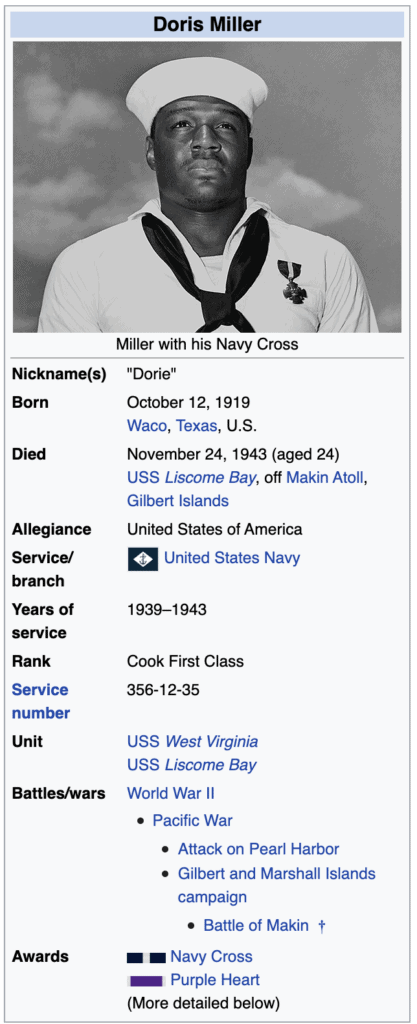

We are still waiting for Doris Miller’s Medal of Honor to be awarded to him posthumously, for saving the lives of countless shipmates during the attack on Pearl Harbor.

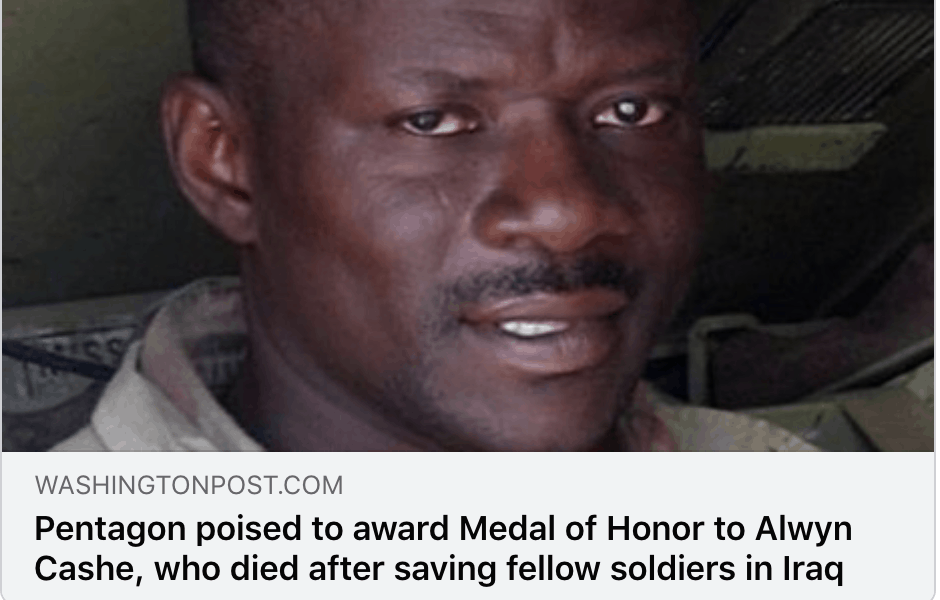

The FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act failed to pass section 584 through the Senate that would have authorized the President of the United States to award the Medal of Honor to Alwyn Cashe for his actions of valor during Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Army Sergeant First Class Alwyn Cashe, an African American veteran, died from his wounds after saving the lives of 6 of his soldiers from a burning vehicle after it was hit by an improvised explosive device (IED).

[Note from editor: On August 28, 2020, the Pentagon announced SFC Cashe may soon become the next Black Medal of Honor recipient. Click here to read the story.

The days where we “hope” a Black soldier gets properly recognized for their heroism are over.

It is time to write to our congressional representatives and senators to have our Black heroes, past and present, properly decorated. It is time for our leaders to take a proper account of the prejudices in their own evaluations of bills that are passed.

Every hero deserves the name, but the Black hero shouldn’t have to wait 50 years.

A Call to Action

Dr. Martin Luther King once said, “Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.”

Everyone is able to do something within their sphere to demand racial equality and equity. Do you want to join the cause to ensure these brave Black heroes get the recognition they deserve?

Visit https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/116/hr5549# and follow the instructions on the page to support the bill for Doris Miller and visit https://www.govtrack.us/congress/members to find out who your local representatives are.

Call and write to them about the importance of honoring our Black veteran heroes by supporting the bills to posthumously award the Medal of Honor to Doris Miller and Alwyn Cashe.

Great article, bring on more!